Numbers Man

Nicholas Felton chronicles the minutiae of everyday life, and makes some quietly affecting bar graphs in the process.

Last year, Nicholas Felton drank 272 cups of coffee, ate 149 vegetables, slept 2814 hours and had a 25.7 per cent chance of wearing a shirt. He knows this because he keeps a record of every banal thing that happens to him and, at the end of the year, turns all that seemingly inconsequential information into a graph-filled booklet the size of a small encyclopaedia volume.

His Feltron Annual Reports (the ‘r’ was added to distinguish between the man and his work) filter life’s most quotidian moments through the lens of a PowerPoint presentation. Yet somehow, they manage to feel more meaningful than the sum of its parts; having a cup of coffee may be a relatively insignificant event on its own, but when viewed through a numerical lens over the course of a year, it begins to tell a story different to the ones we usually tell about ourselves. “At the heart of this project,” the 35-year-old designer says down the line from his New York studio, “is the desire to learn more about myself.” Apparently there’s only so much you can glean about yourself from conscious introspection. Where introspection fails, numbers step in.

Felton has produced a lush, data-centric report of his personal habits for every year since 2005, and each varies slightly in its focus. Some concentrate on mood and interactions, others on places visited and the streets walked down. After deciding what he wants to capture in a given year, Fenton trains himself to recognise a signal and to take an action in response. “First, I need to find something that I'm curious about, be it how many miles I travel in a year, or how my friends and acquaintances view me,” he explains. “Next I need an approach that will allow me to capture my year through this lens.”

Emails sent; days spent with his girlfriend (versus his mother); animals eaten and plants killed: keeping track of all the information is a massive undertaking. Felton took manual notes for his initial reports, but as the complexity of the project began to grow so did his recording techniques. “Last year I commissioned an iPhone app that would buzz at random intervals and ask me to complete a survey,” he says.

Beyond providing him with data to build graphs, the project has taught Felton about his personality. “I find it difficult to self-report on my mood”, he says. By asking his friends, family and acquaintances to provide feedback on his fluctuating emotional state, which he did in 2009, he was able to collect a much richer data set. “After quantifying all of the data, I was able to discern that my average mood was ‘swell’, or about 73.9 per cent happy. I also learned that I am an ambivert, which is someone who does not lean towards introversion or extroversion but falls somewhere in between.”

An artist and designer by trade, Felton tells his story by constructing minimalist infographics. Like the word itself, infographics are compounds, merging numbers, text and geometric form – though, unlike the sterile pie charts of so many AGMs, Felton’s infographics convey a human intimacy, making them unique in the world of numerical communication.

A large portion of Fenton’s life is now taken up with recording and analysis (he spent 241 days working on the upcoming 2012 report), but the project began with a much less ambitious aim: to design a series of charts for a university project. He could have plucked the data from just about anywhere, but decided to mine it from his own life. His reasons were largely practical. “As I began digging through my photos and calendars for the year, I found I could describe much of that year in absolute rather than subjective terms,” he explains. “My calendar told me all the places I had gone out to eat, the website Last.fm kept track of all the music I listened to, and I could dig through my digital photos to learn where and what I had photographed.” Assuming that the project would be of interest to no more than his family and friends, he was shocked when he started receiving emails from strangers about how much they enjoyed reading it.

As quantum mechanics tells us, the act of observing a life necessarily impacts on how you live it. This is a good thing if you’re trying to change something about yourself, but bad if you just want to take a snapshot. To avoid these pitfalls Felton is careful not to tabulate his data before the year’s up, but he does learn from it, resolving to read more books or attend more concerts based on his analysis. Recent reports indicate that he needs to spend more time with his girlfriend, which is probably something he didn’t need a graph to tell him.

It may seem odd for someone who meticulously records how many coffees they drink, but outside of his annual reports Felton doesn’t share all that much about himself – not on social media, and not in magazine profiles. He attributes his trait to getting older and busier. He’s also less obsessed with the detritus of daily life than his Rain Man-like reports may let on. “The primary point is to explore information design and personal data patterns, not to celebrate my life”, he says. “But so long as it's the best material I have, I'll continue to explore it.” He also likes the idea of creating an archive, of sorts, for his family. “I wish my parent's experiences were as accessible to me as mine will be to my children. And I wish the same for everyone else.”

This last point is of particular significance. In 2010, the subject of Felton’s annual report shifted from himself to his father, who had recently passed away at the age of 81. “That fall, my sister and I took care of his estate and sorted through his belongings. In the course of this process, I began noticing an abundance of neatly organised but disjointed pieces of his history, and I had the inclination that I might be able to reconstruct his life through the mementos he left behind. I wanted to remember the way he lived rather than the way he died.”

Turns out Felton’s father was also a meticulous archivist of life’s little things, making him a perfect subject for his son’s data mining. Gleamed from passports, postcards, ticket stubs and even cardiographic EPGs, Felton’s 2010 report is less a sterile taxonomy of his father’s expenses than a touching celebration of a life lived through figures and locations. Charting his life in 10-year increments, the report covers the small (how many months he had a beard in the ‘70s) to the large (his migration from Nazi occupied Berlin) in equal measure.

The trouble with obituaries is the deceased never see how they are celebrated. Asked what his father would have made of having his life pieced together this way, Felton is cautiously optimistic that it might have put his own life in context. “I know that my father was proud of my accomplishments, but I am not sure that he understood my profession. It's my hope that if he were able to view his report, then my work would make more sense to him.”

While reducing his father’s life “to a pile of numbers” made Felton nervous, he hopes that, like his own reports, they expand his father rather than reduce him. “I think I was able to find the right balance of honesty, detail and aggregation to recompile his personality,” he says. “My father's report brings me close to him. The document triggers memories each time I open it.”

- - -

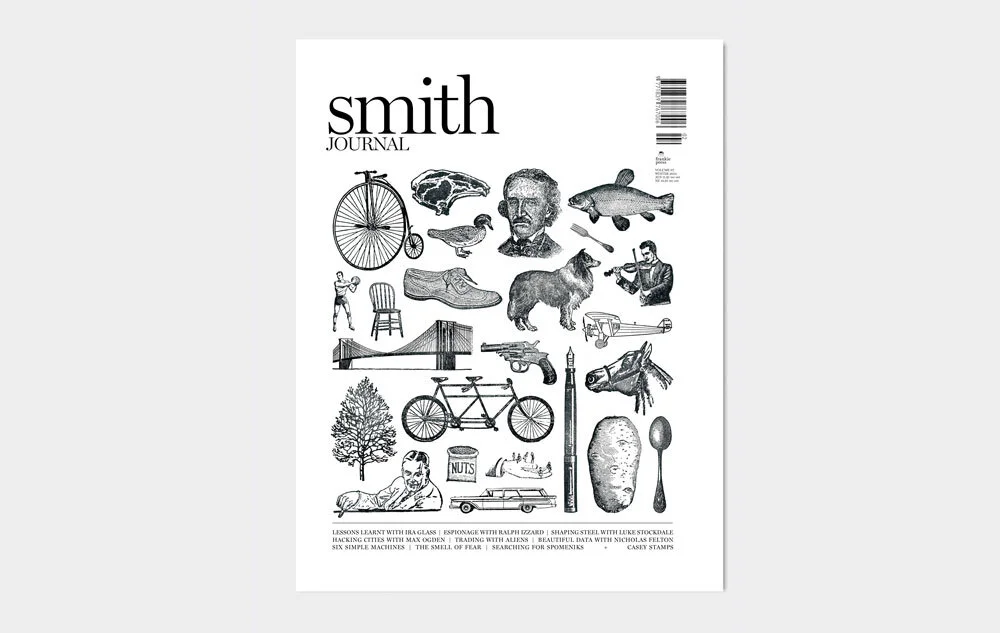

Published in Smith Journal vol. 7 with the title ‘Annual Report’. Photography by Adam Kremer.